Lawsuits in Pennsylvania

What is a lawsuit?

A lawsuit is a formal legal proceeding in which a plaintiff (the party filing the lawsuit) brings a claim against a defendant (the party being filed against) before a court of law. This is done to receive some kind of resolution or remedy for a wrong committed, harm done, or a violation of legal rights.

When to file a lawsuit

If you are facing a legal dispute, it may be time to consider filing a lawsuit. Filing a lawsuit is not a decision to be made lightly. You should consider all of your options before filing. Ask yourself questions like:

- Do I have a good case?—Is there a legal basis for the claim you want to raise? It’s important to understand if there are laws or principles in place that support your case. Not every dispute can be turned into a lawsuit. An experienced attorney can consult with you to review the facts of your case and let you know whether or not a lawsuit is the best path forward.

- Am I open to mediation?—Lawsuits can be time-consuming and expensive. Some disputes are better resolved through alternative means, such as mediation. Mediation involves a neutral third party hearing the facts and attempting to have the parties reach a settlement. This can result in a quicker outcome than a traditional lawsuit and trial would.

- Will a lawsuit provide the resolution I am looking for?—Depending on your resolution goals, a lawsuit may or may not help. It’s important to consider whether the type of resolution you are looking for can come from a lawsuit before filing one.

- Am I prepared to handle the consequences of a lawsuit?—Lawsuits can be emotionally draining. Lawsuits can also have lasting impacts on relationships and, depending on with whom you are having a dispute, they may do more harm than good.

Questions like those listed above are not meant to scare you out of filing suit, but rather to help you decide which type of legal action may be best for your individual situation. Sometimes mediation is better. Sometimes you’ll receive more money from a settlement. Before making any decisions, consult with an experienced attorney. An attorney, like the ones at Cornerstone Law Firm, LLC, can help you decide what legal action to take.

How do I know if I can sue someone?

Part of determining when to file a lawsuit is determining if you can file one. How do you know if you can sue someone? Here are some points to consider:

- Legal basis—Does your claim have a legal basis or cause of action? Research applicable laws and legal principles to see what kind of case you may have.

- Legal standing—Are you directly affected by the proposed defendant’s actions? Do you have a legal right that has been violated? You may be able to file suit.

- Evidence—Do you have evidence to support any claims of harm? It can be physical, financial, emotional, or reputational harm. Having evidence to back up your claim will help.

- Statute of limitations—It’s important to make sure the case you want to bring is still within its legal time limit. Cases that are too old won’t be viable in court.

The best way to determine whether or not you can sue someone is by consulting with an attorney. Experienced attorneys are already familiar with legal bases and legal standings. They can help you to assess your situation and take appropriate action.

Statute of Limitations

Like we mentioned in that last bullet point, the statute of limitations can make a huge impact on what kind of resolution you are able to receive. Different types of cases have different statutes of limitations, and some don’t have any.

In general, most civil law disputes (personal injury, property damage, breach of contract, etc.) have two-to-four-year statutes of limitations. Others, like libel or slander claims, only have one-year statutes. Criminal law works a little differently. Bigger crimes, like murder or sexual assault, don’t have a statute of limitations. Misdemeanors and some felonies can be anywhere from two to five years.

When does the clock start on statutes of limitations?

There are different ways to determine when the statute of limitations has started. It may vary depending on the type of case you have. Some common ways the clock starts are the date of harm, the date you discovered harm, and the date you should have discovered harm.

The “date of harm” refers to the date that started your dispute. If this is a car accident case, the clock would begin on the date of the accident. In other cases, like a breach of contract, you may not notice any harm has been done right away. In cases like that, the clock would start when you discovered the harm. In rare cases, the clock may start on the date you should have discovered the harm.

Can I sue someone after the statute of limitations has run out?

It depends. There may be some instances where the statute of limitations begins later, or where it has been paused. The statute of limitations must be pled as an affirmative defense, or it can be waived. There are times when you can sue and win a case beyond the statute of limitations. In most circumstances, though, once the time limit has been reached, you probably will not have a successful conclusion to a lawsuit.

If you’re not sure about the time limit of your situation, contact Cornerstone Law Firm. We can review the details of your case and let you know if you are still able to file suit.

How to File a Lawsuit

Once you have decided to file a lawsuit, there are steps you must take in order to actually file it.

Filing a Complaint & Issuing a Summons

Most lawsuits are started by filing a Complaint. There are varying filing fees depending on the type of case. The Complaint will explain the claims that the plaintiff is bringing against the defendant. Complaints will be filed with the Court. After filing the Complaint, it must be served to the Defendant to make them aware of the impending lawsuit. Serving the Complaint is often done in one of two ways, according to the type of case being served. It can be sent through certified mail or delivered by a sheriff or constable. Having the Complaint delivered will incur an additional fee, but you may be able to recover the filing and service fees if you win the lawsuit.

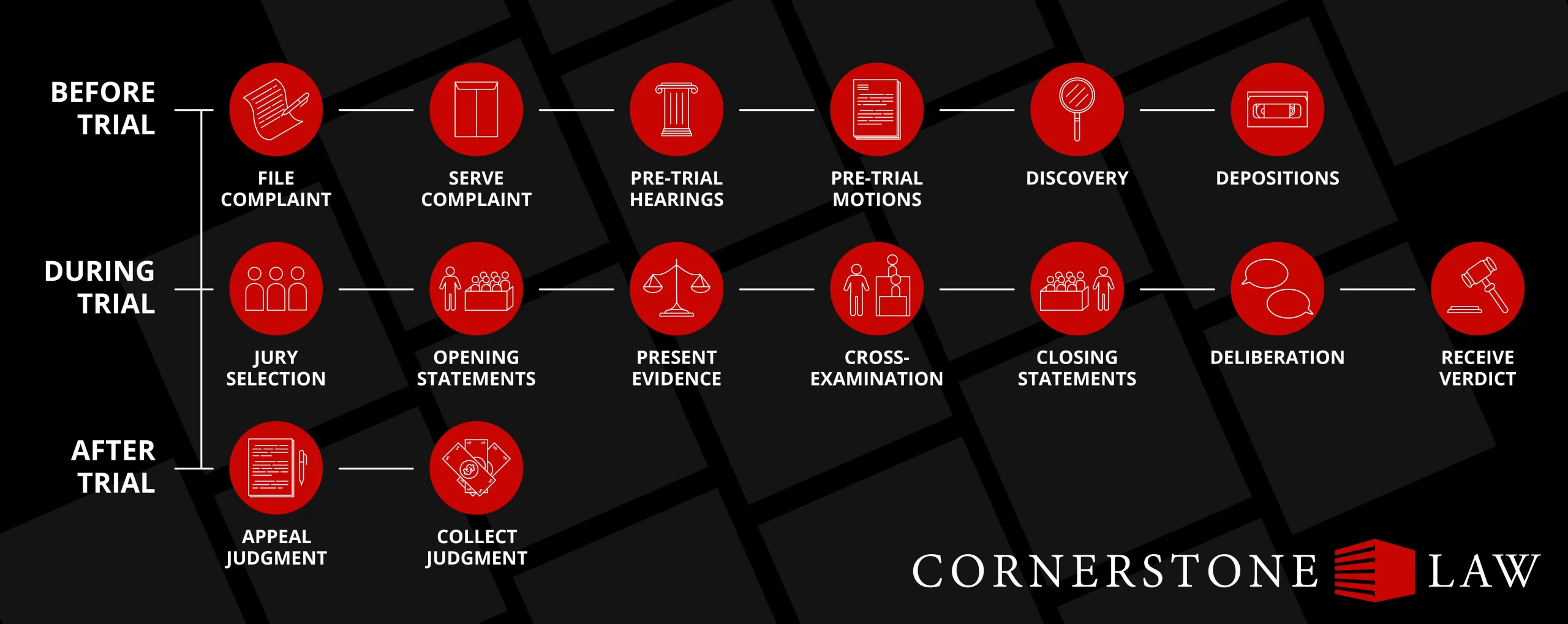

General Steps for Civil Lawsuits

While all lawsuits vary depending on the details, most follow the same general steps. The length of time each step will take is different for each case. Some lawsuits can be resolved within a matter of months, while others may last several years. It’s also important to note that criminal lawsuits differ from civil lawsuits. Below are the general steps for civil suits. You can check out our page on criminal trials to see a timeline for those.

Before Trial

Before trial, both the plaintiff and the defendant will be able to gather evidence to support claims and build either their case or their defense before going before a judge and jury. Depending on the type of case, you will also have to take the following steps:

- Pre-trial Hearings—Pre-trial hearings will allow both sides’ attorneys to discuss the case with the judge. Resolutions can be offered, and pleas can be entered. The judge may issue a date for an additional hearing or set a date for trial.

- Pre-trial Motions—The plaintiff and/or defendant may file pre-trial motions to address legal issues or seek a specific ruling. This may include a motion to dismiss the case, a motion for summary judgment, or a motion to exclude certain evidence.

- Discovery—Both parties gather and exchange evidence and information related to the case. This can include testimonies (both written and recorded), documents, and reports from expert witnesses.

- Depositions—A deposition is when a plaintiff, a defendant, or a witness answers questions under oath. Depositions can be recorded in writing or on video.

During Trial

Once the pre-trial steps have been completed and the date for trial has been set, the trial will commence. A trial can be before a single judge or a jury. Criminal trials usually last for two to three days, and civil trials are usually three to four days. There are, of course, exceptions. The basic steps of a trial include:

- Jury Selection—Potential jurors will be summoned from motor vehicle and voter registration lists. The attorneys and judge will ask these people a series of questions to determine if they have any biases that may impact their ability to serve on the jury. Once the jury is selected, they will be able to move forward with trial. For criminal trials, there are 12 jurors, and for civil trials, there can be anywhere from 6 to 12. In both cases, one or two alternates may be selected in case a juror is unable to serve.

- Opening Statements—At the beginning of the trial, the attorneys for both the plaintiff and the defendant will make their opening statements. This is a time for the attorneys to outline the facts of the case, the issues present, and the arguments they plan to make during trial. They can present their theories about the case and give an overview of the evidence they will present to support the theories. Plaintiffs (and prosecution in criminal trials) have the burden of proof placed on them, so they will often give the first opening statement.

- Presentation of Evidence—After opening statements, both sides can present their evidence. This may include calling witnesses to testify or introducing evidence in the form of documents, photographs, videos, or other exhibits. When calling witnesses, attorneys may directly examine them on the stand, asking them questions that will provide a testimony in favor of that attorney’s position.

- Cross-Examination—This phase of the trial consists of one party’s attorney questioning a witness who has testified for the other party. During cross-examination, the opposing attorney will challenge the credibility of the testimony, point out any inconsistences, or introduce alternative interpretations. Some attorneys may choose to do additional direct examinations and cross-examinations after the first testimony is given and challenged.

- Closing Statements—Once the evidence has been presented and any witnesses have been examined, the attorneys will make their closing statements. Similar to opening statements, the plaintiff/prosecution will typically go first. During these statements, attorneys will summarize the evidence presented and present a persuasive argument to either the judge or jury. This is often an important moment in trials.

- Jury Deliberation—After closing statements, the jury will move to another room for deliberation. Deliberation can last for any length of time, from just a few minutes to a few days. It will often depend on the complexity of the case. In bench trials (where there is no jury and just a judge), the judge will often take a few days to review the case before issuing a decision.

- Verdict—The verdict (also called a judgment) will be entered after deliberation has ended. It is at this point that the trial has officially concluded, and any awards will be ordered. Awards typically include monetary compensation for the dispute, attorneys’ fees, or other fees.

How You Should Act in Court

Courtrooms are serious places. Judges and juries expect a level of civility and professionalism. It’s not uncommon to see shouting and emotional outbursts on TV court dramas, but that isn’t acceptable behavior for real life. Whether you are the plaintiff or the defendant, you should come to court in a calm and courteous manner. Dress appropriately and professionally. While it may feel stressful, especially if you are the defendant, do your best to be as comfortable and polite as possible.

Preponderance of Evidence v. Beyond a Reasonable Doubt

In civil lawsuits, the burden of proof lies with the plaintiff. That means that if you are the individual filing suit, you need to be prepared to prove your argument in order to win. Civil cases require a preponderance of evidence. This means your argument needs to be more believable than the defendant’s. The scales of justice need to be just slightly balanced in your favor.

Civil cases differ from criminal cases in this way. For criminal trials, the prosecutor must prove the defendant’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Prosecutors must therefore convince a judge or jury of the defendant’s guilt. If there are reasonable doubts cast upon a prosecutor’s case, it is more likely that the defendant will win.

After Trial

Appealing the Judgment

After trial, either side may file an appeal. Not every judgment can be appealed, and the appeal process can be lengthy and expensive. It’s important to really assess your case before filing an appeal.

Appeals can provide certain benefits like:

- correcting injustices that occurred as a result of the court’s decision,

- setting new precedents that clarify or change the interpretation of the law, and

- providing additional remedies or relief that were unavailable at the lower court level.

Collecting the Judgment

If you have been awarded a money judgment, there are a few ways you can collect it. The other party can pay you the awarded amount after trial. You can place a lien on their property and foreclose on it, essentially forcing them to sell and pay you with the money from the sale. Or, in some cases, you can get a wage garnishment, and money will be collected from each of their paychecks until the full amount is paid. Both wage garnishments and liens can impact the other person’s credit score.

Common Types of Civil Lawsuits

There are a variety of lawsuits you can file as there are a variety of disputes you can face. Some of the most common types of lawsuits include:

- Car accidents

- Slip and fall incidents

- Premises liability claims

- Medical malpractice

- Product liability (defective products)

- Product recalls

- Workplace accidents

- Wrongful termination

- Employment discrimination/Harassment

- Wage & hour violations

- Breach of contract

- Workplace retaliation

- Whistleblower claims

- Class action lawsuits

- Unfair competition

- Property damage

- Mortgage foreclosures

- Construction defects

- Landlord/tenant disputes

- Insurance disputes

- Intellectual property infringement

- Copyright/Trademark infringement

- Patent disputes

- Trade secret misappropriation

- Professional malpractice (e.g., legal malpractice, accounting malpractice)

- Fraud

- Defamation (libel or slander)

- Breach of fiduciary duty

- Shareholder disputes

- Partnership disputes

- Securities fraud

- Antitrust violations

- Breach of warranty

- Consumer fraud

- Environmental law violations

- Civil rights violations

- Police misconduct

- School-related disputes (e.g., bullying, discrimination)

- Privacy violations

- Discrimination in public accommodations

- Family law disputes (e.g., divorce, child custody)

- Adoption-related issues

- Paternity disputes

- Probate disputes

- Estate planning mistakes

- Immigration law disputes

- Bankruptcy disputes

- Professional licensing disputes

- Violation of constitutional rights

Levels of Court in Pennsylvania

Different states have different levels of court. In Pennsylvania, those consist of the following:

- Magisterial District Court—This is the lowest level of court in Pennsylvania. Cases heard on this level include minor criminal offenses (summary offenses), traffic violations, landlord/tenant disputes, and civil cases with smaller monetary amounts.

- Court of Common Pleas—This is the next highest court level, and the primary trial court for Pennsylvania. Cases heard here include a range of civil and criminal cases, like serious criminal offenses, family law matters, probate issues, and more.

- Superior Court—This is an intermediate appellate court. The Superior Court primarily handles appeals from the Court of Common Pleas. Cases can range from civil, criminal, and family law matters. The Superior Court can affirm, reverse, modify, or remand decisions made by the lower courts.

- Commonwealth Court—This is another intermediate appellate court. The Commonwealth Court primarily handles disputes with state and local government agencies. These can include administrative law, tax issues, zoning appeals, and election disputes.

- Supreme Court of Pennsylvania—This is the highest court in the state of Pennsylvania. It is the final appellate court and has discretionary review powers (meaning it can choose which cases to hear). This court focuses on reviewing constitutional issues and legal questions. Decisions made at this level can create legal precedent for the whole state.

There are some additional specialized courts in Pennsylvania as well. These include the Orphans’ Court (focused on estates, wills, and trusts) and the Philadelphia Municipal Court (focused on civil and criminal cases within Philadelphia).

Depending on where you file your lawsuit, you can appeal the judgment to a higher level of court. If you make it all the way to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania and still wish to file an appeal, you will have to file it with the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS). Similar to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, SCOTUS has discretionary review and only hears a limited number of cases every year.